Sri Lanka, known for its exceptional cultural and religious diversity, boasts a vibrant tapestry of beliefs and practices. However, the country also fights with complex elements around the right to belief and practice of religion, especially when it comes to minority religions versus the majority. This article looks into the insights of the right to belief and the right to practice religion in Sri Lanka and decodes the discrepancies that exist within the framework of the state system.

The right to belief is a fundamental human right, entrenching individuals the freedom to hold and express their religious convictions. In Sri Lanka, this right is enshrined in the 1978 constitution, which recognizes Buddhism as the primary religion while ensuring protection for other religions. However, the realistic application of this fundamental right varies for minorities’ and the majority religion.

For the majority religion, Buddhism, Sri Lanka’s constitution accords a privileged status. Buddhism is granted special recognition, with the state perceiving the responsibility of promoting and fostering its teachings. Consequently, this can create an atmosphere where Buddhism is discerned as the dominant faith, potentially disparaging minority religions.

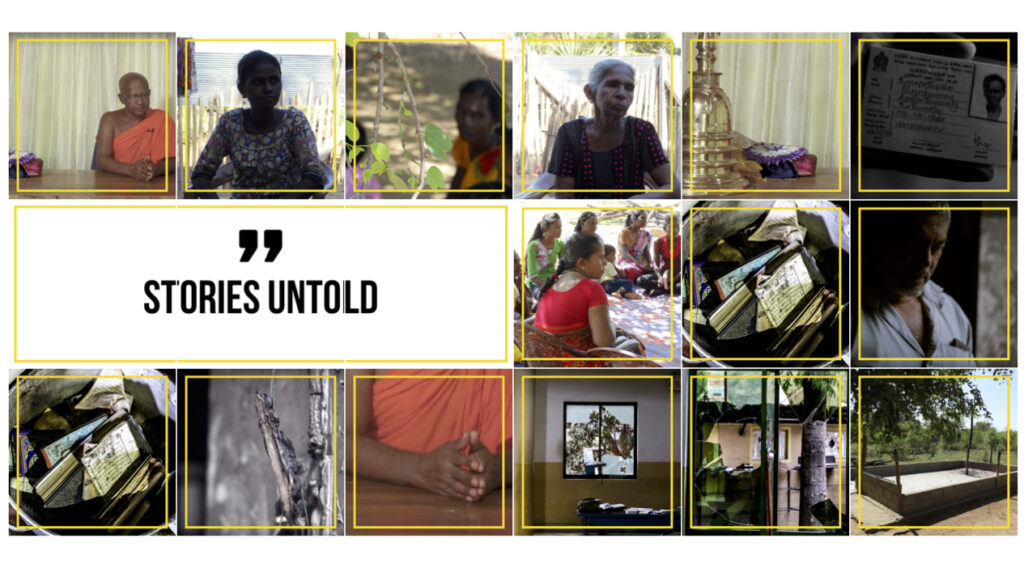

Besides, minority religions such as Islam and Christianity face obstacles in the practice of their right to belief. Even though the Constitution entrenches equal protection, the practice of reality reveals instances of intolerance, prejudice, and even violence against religious minorities. These incidents not only violate upon their right to belief but also curtail their ability to liberally express and promulgate their faith.

Another distressing issue that religious minorities try to combat is the occasional outbreak of violence targeting their places of worship and religious gatherings. Mosques, churches, and other religious sites have been subject to attacks, leading to loss of lives, destruction of property, and an omnipresent atmosphere of fear within these communities and ethnicities at large. Such acts of violence not only infringe upon the right to practice religion but also affects at the core of religious identity, leaving generational scars on the affected groups of people.

While the right to belief forms the skeleton, the right to practice religion involves the manifestation and spectacles of religious rituals, traditions, and customs. In Sri Lanka, the right to practice religion differs significantly for minority and predominant religions. For the majority Buddhist community, practising their faith is relatively unrestricted. Temples, vihara, and Buddhist monuments are archaeologically visible throughout the country, and Buddhist festivals are celebrated with great pomp and splendour by government institutions. The state actively supports and invests in the preservation and promotion of Buddhist heritage sites, providing ample resources and protection with the empowerment of state institutions such as the Department of Archaeology.

In contrast, minority religions face various provocations in practising their faith. Places of worship for Hindus, Muslims, and Christians are not always accorded the same level of state protection or glorification. There have been occasions of attacks on mosques, churches, and temples of minority religions, disrupting religious practices and infusing a sense of fear within these communities.

Furthermore, minority religious groups face hurdles in acquiring permits to build new places of worship, facing bureaucratic procedures and societal hesitance and resistance. This limits their ability to broaden and grow their religious communities.

While Sri Lanka’s constitution enshrines the right to belief and practice religion for all its citizens, the ground-level practice often diverts from this ideal. The concessions and prominence awarded to the majority religion, Buddhism, can adequately marginalize minority religions, hampering their ability to willingly practice their faith. Discrimination, violence, and systemic obstacles faced by religious minorities portray a distinct contrast to the proportional unrestrained practice of the majority religion. Moving forward, it is pivotal for Sri Lanka to bridge these inconsistencies, cultivating an environment that nourishes and safeguards the right to belief and practice religion for all its mixed religious communities. Only then can true religious consonance and Religious freedom be achieved in the country.