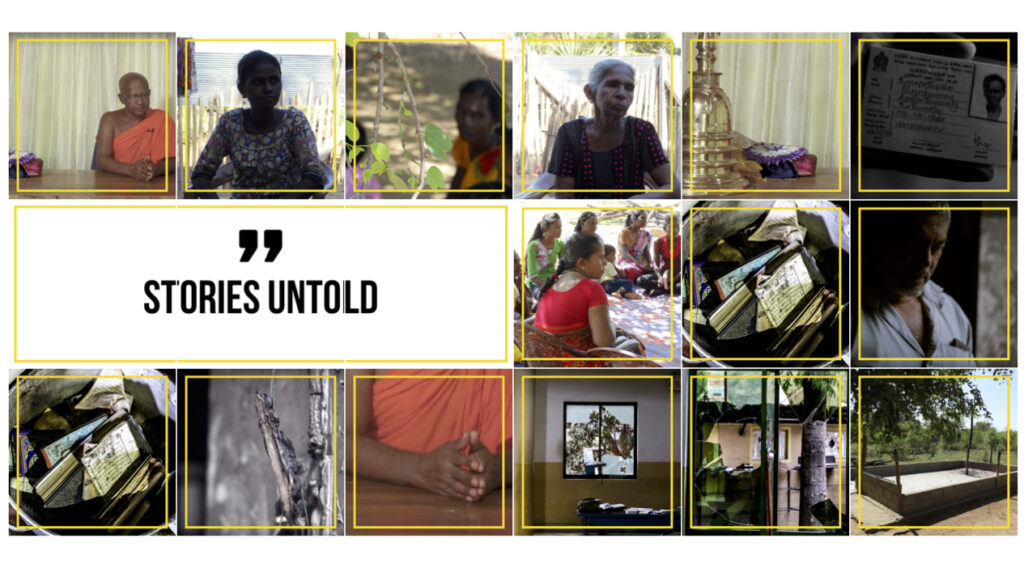

Hindutva, an ideology first coined by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar in 1923, envisions India as a Hindu homeland rooted in shared ancestry, culture, and reverence for India as both fatherland and holy land. While tolerant of indigenous religions like Sikhism and Jainism, it views Islam and Christianity as foreign impositions. Inspired partly by European nationalism, Hindutva departed from traditional Hindu spiritualism, evolving into a politicized and militant movement. The ideology entered mainstream politics via the BJP, culminating in Narendra Modi’s rise to power in 2014. Hindutva’s core planks cow protection, anti-conversion laws, and aggressive nationalism have sometimes manifested in misogyny, moral policing, and online vilification of dissenters, especially targeting women who refuse the subservient role it imposes on them.

In Sri Lanka, Hindutva’s local face emerged in 2016 with the founding of Siva Senai, led by Maravanpulavu Sachchithananthan in Vavuniya. Informally supported by India’s RSS and Shiv Sena, it claims to protect Tamil Hindus from conversion and Sinhalese-Buddhist encroachment, promotes anti-conversion laws, and rebrands traditional Tamil homelands in the North and East as “Sivabhoomi” (Land of Shiva). This marks a radical shift from Sri Lanka’s historically secular Tamil nationalism historically rooted in language and culture toward a religion-centered identity that sidelines non-Hindu Tamils.

Siva Senai celebrates BJP electoral victories in India as universal Tamil Hindu triumphs. Yet, Modi’s latest victory in 2024 was only achieved via coalition, hinting at declining Hindutva dominance in India’s political landscape. In Sri Lanka, however, the movement is gaining traction, in part due to the Tamil community’s disunity. The LTTE’s strategy of eliminating any rival Tamil leadership it viewed as a threat resulted in the dearth of political leadership and vision for the community’s future post-war. As the fragmented Tamil leadership struggled to articulate coherent policy, extremists pounced on the opportunity to fill the vacuum, presenting Hindutva as a politically viable alternative to unify the disparate segments of Tamil society, desperate for any roadmap to replace the failed dream of Eelam.

Post-war state interventions in historically Tamil areas in the North and East military land seizures, temple construction, and bureaucracy have fueled resentment among minority communities. Siva Senai capitalizes on these tensions by positioning itself as the sole defender of Tamil Hindu rights, opposing Buddhisization and military expansion in the North and East. The group is highly active online, using social media and private groups to spread propaganda and mobilize members.

Recent incidents highlight the movement’s focus:

- Feb 2023: Rudra Sena leaflets accuse Christians and Muslims of unethical conversions.

- Apr 2024: Posters in Mannar warn Christians not to erect festival arches.

- May 2024: Jaffna rallies condemn Muslims for cattle slaughter.

- July 2024: Protests demand the removal of a Christian education director.

Siva Senai frames Tamil Christians as “race traitors” and “colonial remnants,” echoing Sinhala-Buddhist nationalist rhetoric that excludes non-Buddhists from an exclusive Sinhala identity. Its leader uses derogatory terms to denigrate Christian politicians, and the group pressures police to shut down public Christian events, and opposes traditional Catholic festivals, claiming they supplant and replace Hindu religious celebrations. The movement’s escalating rhetoric raises fears of potential violence, drawing ominous parallels with Hindutva-inspired attacks on Christians in India.

Historically, Sri Lankan Hinduism has been rooted in Shaivism an inclusive, egalitarian South Indian tradition distinct from Hindutva’s caste conscious Vaishnavism originating in North India. Hindutva’s exclusivist nature is alien to Sri Lanka’s indigenous Tamil culture, but its similarity to Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism offers a blueprint to achieve ethno-religious political unity that Tamil extremists find appealing in the post-war ideological vacuum.

Hindutva has evolved from being an invasive alien ideology, and has since been reshaped to meet local challenges and conditions war trauma, military occupation, land disputes, and cultural erosion. The danger lies not only in its divisive rhetoric deepening rifts within Sri Lanka’s fragmented Tamil minority split geographically into distinct Northern, Eastern, hill country, and urban communities but in its potential to fracture an already vulnerable ethnic group even further along religious lines, with only extremists among Tamil, Sinhala-Buddhist, and Muslim political interests standing to gain from the community’s schism.

If Tamil political leadership fails to inspire the community with a compelling vision for the future, Hindutva’s tenet of “Sivabhoomi” may become permanently entrenched in the zeitgeist redefining Tamil identity in purely religious terms by replacing centuries of inclusive secular Tamil nationalism with exclusive religious identity politics, and casting a divisive shadow over the nation that threatens Sri Lanka’s nascent pluralist fabric.